Scott Skinner has one of the most unique collections of Japanese prints in the world because of his focus on collecting prints with kite images. This collection, however, does not have a corner on uniqueness, as we know of a Seattle collector of Japanese prints who collects only prints with images of cameras.. The point is, when collecting, one should have a focus, trying not to stray too far from the subject matter, so that you build a strong base for the collection. Within his own collection, Scott has discovered another “style” of Japanese printing, a format which is interactive. And we ask, how does one interact with a Japanese kite print? Follow along and find out.

I’ve been working hard to organize all of the kite prints in my collection, especially the Japanese ukiyo-e that were not included in John Stevenson’s Japanese Kite Prints. I’ve found images that I had forgotten about, have been able to organize prints by subject, and am now able to ensure that the prints are safe and archivally stable. For those unfamiliar with ukiyo-e prints, they are a style of Japanese wood block printing, produced between the 17th and 20th centuries which were mass produced and therefore more affordable. Literally translated, ukiyo-e means “floating world” and the prints generally depicted landscapes, stories from history, or images of city life often featuring popular actors engaged in activities of leisure.

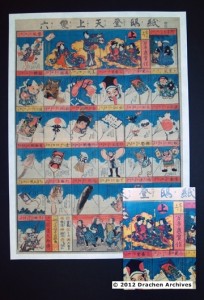

In addition to the straightforward ‘images of the floating world’ that might include city-scapes, views of Fuji, warring heroes and kabuki actors, there are other types of ukiyo-e that I’ve run across in my collecting journey. One type is the sugoroku, which is printed in a game-board format. Played like Chutes and Ladders, it was a common New Year’s gift that would have been played year-round by Japanese families. The sugoroku journeys might have been to scenic spots around Edo, locales along the Tokaido Road, or, in one case, a tour of Edo kite shapes and themes. (The picture below shows the print and book Soaring Kite Sugoroku).

In my recent organizing I have found two prints (three panels each) that were very interesting and that illustrate a type of ukiyo-e that I was previously unfamiliar with. One is a straightforward view of a kabuki play, but the other is a little like the sugoroku; it’s a view of the same moment in time, but meant to be cut apart and made into a diorama.

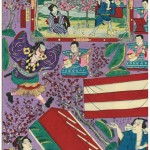

Both prints depict a famous scene from a play, “Kin Shachi Uwasano Takanami Yakko-dako chunori no ba”, which tells the famous story of Kakinoke Kinsuke, who flew over the walls of Nagoya castle to steal the scales from the golden dolphins on top of the roof. The first is a very straightforward triptych (three panel print), accurately showing a moment in the play in which Kinsuke flies as a yakko kite. Included in the depiction are four actors, musicians, stage, and background. For adults in Japan, the detailed image would immediately convey the Kinsuke story. The famous Kabuki actor, Onoe Kikugoro plays Kinsuke. Any time I see an actor portraying a yakko kite, I’m reminded of the Soga Brothers’ play, that John Stevenson so accurately described in Japanese Kite Prints (prints 58 and 59): Yakko Takohei, Mr Yakko kite was not an original character in the play, but one who became popular in New Year’s performances.

The second print is, in my opinion, even more interesting. It is an example of a tatebanko, a paper diorama that is a type of omocha-e, a woodblock print designed to be cut apart and played with. As you can see, the tatebanko depicts the same play, but this time, with the full and realistic backdrop to the event; the Nagoya castle and its environment, the primary players, including Kinsuke, theater musicians, the castle moat, and blooming cherry trees. All the pieces can be cut out and put together as shown in the middle of the print.

As you can imagine, the tatebanko was primarily a child’s plaything and parents could use it to tell the story depicted and talk to their children about the attributes and values of the characters. A tatebanko might be the first gift of a New Year to bring good luck to the family’s children. Nobuhiko Yoshizumi, Kyoto’s knowledgeable and skilled kite maker has given me many of the details related here and he also sent other examples of tatebanko. As you can see, the tatebanko not only depict many of the famous moments in kabuki theater, they also accurately show everyday details from Japanese life at the end of the Edo period and into the Meiji period. In the elaborate scenes, you find details of homes, their gardens, elaborate clothing of the upper classes, as well as weapons, musical instruments, and animals.

As you can imagine, the tatebanko was primarily a child’s plaything and parents could use it to tell the story depicted and talk to their children about the attributes and values of the characters. A tatebanko might be the first gift of a New Year to bring good luck to the family’s children. Nobuhiko Yoshizumi, Kyoto’s knowledgeable and skilled kite maker has given me many of the details related here and he also sent other examples of tatebanko. As you can see, the tatebanko not only depict many of the famous moments in kabuki theater, they also accurately show everyday details from Japanese life at the end of the Edo period and into the Meiji period. In the elaborate scenes, you find details of homes, their gardens, elaborate clothing of the upper classes, as well as weapons, musical instruments, and animals.

In writing this article for Kitelife, I had Ali Fujino, Administrator of the Drachen Foundation upload the Kabuki and Tatebanko prints into the Foundation Collection Database. You can do the same with interesting items in your collections; establish a user name and password, go to the Collections page and find the tab, ‘add an item’, then follow the upload directions to create a space for your item.

Scott Skinner