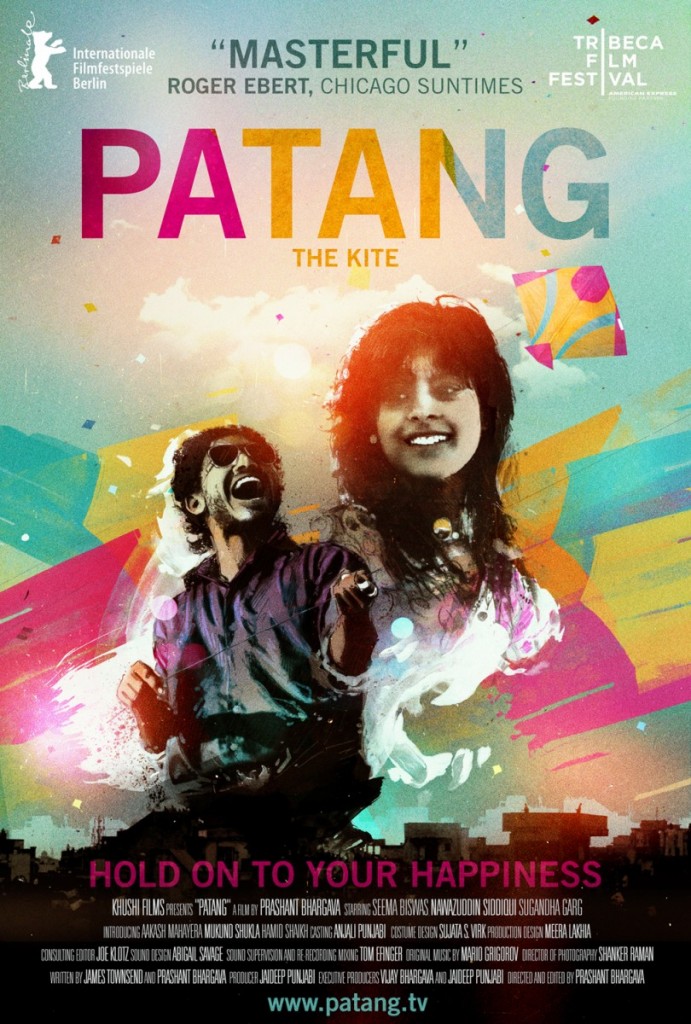

95 Minutes, 2012, USA/India

In the old city of Ahmedabad, amid India’s largest kite festival, a family duels, spins and soars like the countless kites in the skies above.

When a Delhi businessman returns to his childhood home in Ahmedabad for India’s largest kite festival, an entire family has to confront its own fractured past and fragile dreams. With naturalistic performances from actors and non-actors alike, bold, lyrical editing and vibrant cinematography, PATANG delights the senses and nourishes the spirit.

A poetic journey to the old city of Ahmedabad, PATANG weaves together the stories of six people transformed by the energy of India’s largest kite festival.

Every year a million kites fill the skies above Ahmedabad-dueling, soaring, tumbling and flying high. When a successful Delhi businessman takes his daughter on a surprise trip back to his childhood home for the festival, an entire family has to confront its own fractured past and fragile dreams.

Music and fireworks, food and laughter, a kaleidoscope of color and light, the magic of the kite flying high – a traditional recipe of healing and renewal.

With naturalistic performances from actors and non-actors alike, bold, lyrical editing, vibrant cinematography and a kinetic score, Patang delights the senses and nourishes the spirit.

ABOUT AHMEDABAD’S KITE FESTIVAL

In India, kite flying is more than a pastime or sport. It is a fiercely competitive national obsession.

On January 14th, the city of Ahmedabad is possessed by the spirit of Uttarayan, the largest kite festival in India. According to the Hindu calendar, it is the day fondly known as the day the wind direction changes.

Four million kites are stacked and sold. At sunrise, rich and poor, Hindu and Muslim, young and old, flood their rooftops battling to cut their neighbor’s kite. Amidst the sighs of defeat and the screams of victory all eyes are fixed on the vibrant spectacle above.

Once the sun sets the trees are littered with a million fallen kites. Serious kite fliers begin their final competition launching lanterns (tukkals) attached to their kite strings. With fireworks flooding the skies this marks the end of the festival.

Kites are over one thousand years old in India. The poet Manzan used the word ‘patang’, the more common word for kite, in his poem of 1542 A.D.

PATANG & THE NEW WAVE OF INDIAN CINEMA

A new movement has emerged in Indian cinema in recent years, led by filmmakers determined to tell fiercely independent stories that provide honest reflections of contemporary Indian life. PATANG, the only Indian film to premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival’s Forum program, stands as a shining example, pushing the boundaries of the movement with its naturalistic performances, novel cinematic language and message of celebration and healing. This fresh, unvarnished take on India, as seen in other such movies as Dhobi Gaat, Peepli Live, Vihir, Udaan and Love Sex Aur Dhokha, has been embraced by audiences and critics around the world.

ABOUT THE DIRECTOR

Seven years in the making, PATANG is Prashant Bhargava’s first feature film. His short film SANGAM premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, garnering several awards and distinctions. The film was distributed by Film Movement and MUBI and broadcast on Arte/ZDF, The Sundance Channel and PBS. Prashant started out in the arts as a graffiti artist in his hometown of Chicago. He went on to study computer science at Cornell University and theatrical directing at The Actors Studio MFA program. For the past fifteen years, he has directed and designed commercials, music videos, title sequences and promos. Prashant’s next film is entitled the HIGHLANDS

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT

The seeds for the movie Patang were based on the memories of my uncles dueling kites. In India kite flying transcends boundaries. Rich or poor, Hindu or Muslim, young or old – together they look towards the sky with wonder, thoughts and doubts forgotten. Kite flying is meditation in its simplest form.

In 2005, I visited Ahmedabad to experience their annual kite festival, the largest in India. When I first witnessed the entire city on their rooftops, staring up at the sky, their kites dueling ferociously, dancing without inhibition, I knew I had to make this film in Ahmedabad.

Inspired by the spiritual energy of the festival, I returned the next three years, slowly immersing myself in the ways of the old city. I became acquainted with its unwritten codes of conduct, its rhythms and secrets. I would sit on a street corner for hours at a stretch and just observe. Over time, I connected with shopkeepers and street kids, gangsters and grandmothers. This process formed the foundation for my characters, story and my approach to shooting the film.

I found myself discovering stories within Ahmedabad’s old city that intrigued me. Fractured relationships, property disputes, the meaning of home and the spirit of celebration were recurring themes that surfaced.

Patang’s joyful message and its cinematic magic developed organically. My desire was for the sense of poetry and aesthetics to be less of an imposed perspective and more of a view that emerged from the pride of the people and place.

Seven years in the making, Patang has been a journey which has inspired and brought together many. The key theme of resilience of family is reflected by the bonds between all of us who gave our hearts to make the film.

PRODUCTION NOTES

The seeds for the movie Patang were planted in 2005, when director Prashant Bhargava traveled to Ahmedabad to experience the city’s annual kite festival. “When I first witnessed the entire city on their rooftops, staring up at the sky, their kites dueling ferociously, dancing without inhibition, I had to make this film.”

Inspired by the spiritual energy of the festival, he returned the next three years, documenting his experiences with over a hundred hours of video footage. Slowly immersing himself in the ways of the old city, he became acquainted with its unwritten codes of conduct, its rhythms and secrets. Prashant would sit on a street corner for hours at a stretch and just observe. Over time, he connected with shopkeepers and street kids, gangsters and grandmothers. This process formed the foundation for developing the characters and story. As he began to write the script, Prashant realized that capturing the spirit of the festival and the city-its beauty and flow, joy and strength, healing and transcendence-would require multiple narratives. And so Patang found its shape as three interwoven stories centering on a family that reunites for the kite festival.

Shot on location with a cast of both non-actors and professionals, Patang draws from the neo-realist tradition. Preserving the naturalism of the environment guided every decision during filming, from shooting style to crew size to the process with the actors. The owner of the camera store, who ended up playing Bobby’s father, continued to conduct business during the two days of shooting at his shop. Having become a familiar presence in the old city proved indispensable in other ways as well. Prashant recalls, “We had a rapport and support from the politicians, police officers, gambling bookies, the shopkeepers and the grandmothers from my years of research.”

To encourage that naturalism and immediacy for the family scenes, Prashant inspired both his cast and crew to just live together–eat, talk, laugh, fight. Rooftop sequences were created with a group of friends, non-actors who had been flying kites together for thirty years. Renowned actor Seema Biswas co-hosted these celebrations in character, actively helping to prepare meals. Prashant had the cast improvise, shooting them in long takes. With the cameras rolling, he would whisper their objectives to them, to bring out the dramatic elements of the scene. Shanker Raman, director of photography, and Prashant shot simultaneously with two small HD cameras. Both would approach shooting as actors themselves, quiety dancing between the actor’s performances.

Patang’s joyful message and its cinematic magic developed organically from the deep roots in the life of the old city that Prashant had so carefully cultivated: “The sense of poetry and aesthetics became less of an imposed perspective and more of a view that emerged from the pride of the people and place.”

You have yet to see what we really are. Our love and the true spirit of Ahmedabad. – BOBBY

(Excerpt of dialogue from PATANG)

INTERVIEW WITH THE DIRECTOR

How did you cast and work with the kids in the film?

During my visits to Ahmedabad over the years to research the movie, I had befriended several kids—played with them, flew kites with them, got to know their families. Each year, I was certain I had found our lead child actor. But when I returned the next year, they had grown and changed.

A few months prior to the shoot, our casting department selected sixty children. Eventually, we conducted a workshop with twelve children. We played theater games to build trust, discipline and freedom in front of the camera. Many of the children had seen adversity in their past, yet their smiles and laughter were pure. We chose Hamid as our lead child actor, because he was so effortless in front of the camera; he had an uncanny wisdom and persistence in his expression.

During the shoot, we never shared the script with the kids. I would just give them physical tasks. For instance, I would direct Hamid to catch ten cut kites as they fell from the skies above. He’d run through traffic, revel as he caught one, fight with rickshaw drivers as he darted in front of them.

The kids never acted; they were always themselves. Their work shines in the film and sets the bar for the performances by the established actors. Working with the kids was amongst the most exhilarating and rewarding experiences of my life. I learned so much from them as a human being and director.

Discuss your approach to shooting PATANG and the film’s cinematography.

During the three years of research, we accumulated over 100 hours of research footage. We would sit for hours with a camera in hand on a corner, in a shop, in a home or on a rooftop. Beautiful stories would unfold as we silently observed. We slowly let go of our preconceptions. By the third year, we were orchestrating locals to naturally enact scenes of the film. The visual language originated from this immersion and observation.

I was fortunate to collaborate with Shanker Raman (Harud, Peepli Live), our director of photography. He took a leap of faith, embracing the uncertainty inherent in the process. He has a peaceful aura about him on the shoot more akin to a documentary cinematographer. I communicated with him as I would with an actor, providing emotional objectives rather than framing.

We did whatever we could to help the actors to forget about the presence of the cameras. We shot in natural light for the daytime scenes, during early morning or late afternoon. For interior and nighttime scenes, Shanker designed lighting setups that allowed the actors to move freely.

Both Shanker and I were shooting with small HD cameras, so we could do long takes upward of forty minutes. Many times we found ourselves pushing one another out of the way. As time progressed we developed our own rhythm with the actors. Shanker focused on the overall coverage of the drama, and I would capture small moments and experiment freely. We had an unspoken sense of when the magic would occur.

Discuss your process working with composer Mario Grigorov of the Oscar-nominated film Precious to create the film’s score.

Mario Grigorov (Precious, Taxi to the Dark Side) was a blessing, a joy to work with; his palate is incredibly diverse. My vision was to create a theme-driven score that tied together the fate of all the characters. We began in a novel way. We sat together for a week and composed the entire score together on the piano. We developed a theme and melodies that highlighted the journey of the kite and the troubled past of the family. Mario led musicians in improvisations based on these melodies—little of the piano remained in the final score. Mario’s work brought depth and clarity to the narrative.

We then collaborated with legendary vocalist Shubha Mudgal for the final two pieces of the score. After we discussed the emotional journey of each scene with her, she sang atop Mario’s melodies remotely from India. Her voice is delightful and soulful, guiding the destinies of the characters.

Discuss the process behind editing PATANG.

Scenes were not rehearsed; they were improvised largely with non-actors and shot hand-held in long takes, without the conventional over-the-shoulder or master shots. As a result, the edit was a two-year process of distilling and constructing a scripted narrative from 200 hours of documentary-like footage. Just watching the footage took over a month. We would have more than a hundred minutes of footage for each minute of screen time. It was a joy in retrospect but very difficult being in a room by myself.

I began by constructing those scenes with major plot points and then proceeded to the transitional scenes. I would make small discoveries, pulling a shot from here, splicing it with a magic moment there, and then returning to the overall structure. Eventually the edit captured the narrative of the original script.

During the last two months of the process, I worked with the talented editor Joe Klotz (Precious, Rabbit Hole, Junebug) to cut down the two-and-a-half-hour rough cut. We’d go back and forth, revising the larger structure, pacing scenes, preserving the environment and the voice of the film.

The editing was challenging, but it was the part of the process where I grew most as a director.

Which filmmakers have inspired you?

My inspirations… the poetry and depth of the work of Satyajit Ray, Terrence Malick and Lynne Ramsay. The visual flair of Wong Kar-Wai. The naturalistic dramas of Mike Leigh and the Dardenne brothers. I love the work of Jia Zhangke. I could go on forever.

What was the response of the community in which you filmed PATANG when they saw the finished film?

Returning to Ahmedabad to share the film with our cast and crew and the community was a magical experience. I felt honored and humbled when people from Ahmedabad embraced the film as their own story.

Audience members remarked how the film gave their lives and city an identity and a voice and captured the living heritage of their home.

The passion we sought to communicate with the film filled the air as we screened it and then celebrated the kite festival together. So many lives have been affected during the journey of making this film. I hold the memories and the friendships very dear. Sheer family and love.

What are the challenges of making the kind of cinema you would like to make?

We broke every possible rule in making this film. We created a subtle, understated family drama. We shot in a foreign language for the international market. We shot using hand-held cameras with no storyboards, doing improvised takes with largely non-actors.

The crew had to take a leap of faith. We chose to work within the community and preserve the simple and natural beauty found within Ahmedabad’s old city. So often during the process, we were told that what we were trying to do was crazy. And it was. Yet somehow we managed to persevere and make it happen.

**All information and images from press kit at www.patang.tv **