This kite design challenged us more than any other we ever set out to create. Our main purpose with the Tekaweya was to explore the contest between weight and drag reduction in sport kites. Our premise was that reducing drag would pay off in a wide wind range without sacrificing durability or branding the kite as merely an ultralight.

Beyond the technical aspects of the design, we sought to achieve a kite that would be very nimble for its size. So we selected wing geometry that resulted in tight, fast turning and an ability to perform serious ground work.

The depth of the sail is analogous to the frontal profile of an aircraft wing. Increasing sail depth, or frontal profile, results in increased drag but can also improve the kite’s tracking. We found that other drag reduction measures more than offset the slight drag increase resulting from a deep sail.

Controlled Tension

After some experimentation we found that a wingtip vent could be effective at eliminating trailing edge buzz, a major source of aerodynamic drag. Optimally implementing this venting technique implied that we would have to carefully control cloth tension throughout the sail and especially the trailing edge.

You’ll notice that the vents interface parts of the sail that are under different amounts of tension. The trailing edge, including the hem added to the mesh, is held under the greatest tension to minimize vibration.

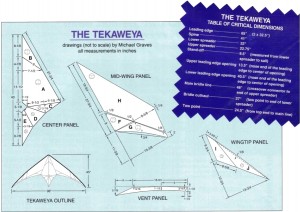

At first glance there appears to be an inordinate number of sail panels (22 in all) in the Tekaweya, but each has a specific purpose, some admittedly only cosmetic.

The large pieces at the spine and midwing allow the cloth to act naturally, taking advantage an efficient airfoil shape. Each of the smaller pieces along the trailing edge take up tension in a specific direction.

There are three stages to creaking down a sail into optimal pattern pieces: areas on the straight again, the bias and the seams.

Most kitemakers understand straight vs bias placement of cloth, but seams are often overlooked as part of the same equation. Where stretch is desired under load we use cloth placement along the bias. Where an area needs to be more dimensionally stable, we align it with the straight gain of the cloth, though even the straight grain still stretches. To really lock in a particular dimension we make sure there is a seam along that distance to take up whatever stress is being placed on the sail.

One of the other features of the Tekaweya is the “Dacron-free” crossover opening (the area where the spine and lower spreaders meet). From previous experience we knew that the crossover opening is an area of the sail that can see some abuse. Given the balanced tension of our sail plan, we were able to design an opening that needs no reinforcement, making it faster and easier to build. This opening can survive hard nose-down crashes or complete collapse of tension on half of the sail without risk of tearing.

Selecting the Frame

The frame provides the force needed to maintain the sail tension through curvature of the leading edge and lower spreaders. This design was created to use a type of wrapped carbon tube that is no longer available commercially. However, we have had satisfactory results using other carbon tubes with a relative stiffness of approximately 0.95 (see Kite Lines Winter-Spring 1995 for a comparison of spars).

Frame selection makes a huge difference in performance. An insufficiently stiff frame won’t sustain the tension desired in the sail. Conversely, an overly stiff frame may be too brittle to take the pounding that can be given to the long, unsupported wingtip during groundwork. As a practical matter we prefer a frame that errs on the flexible side, offering increased durability, though at the expense of upper wind range.

Materials:

- 1.5 yards of main color Carrington K-42 cloth*

- 0.5 yard each of two contrasting colors of Carrington K-42*

- 4.5 yards of 2” Dacron polyester leading edge strip. Cut this into one 2” x 2” piece shaped to fit along the spine at the upper spreader; 2pieces 1-1/4” x 1-1/4” for the stand-off reinforcements; and one 3/8” x 13” piece to reinforce the spine seam below the lower spreader.

- 1.5 yards of 1.5-oz nylon strip 1” wide

- 12” x 3” ballistic nylon for nose reinforcement. From this cut 2 pieces 1” x 1-1/4” for wingtip reinforcements.

- 2” x 1.5” adhesive-backed Kevlar tape for nose reinforcement.

- 3” x 1/4” lightweight lace or ribbon

- 8” x 28” fiberglass window screen

- 9 carbon fiber tubes 32.5” long (we suggest Avia Sport 2200, Skyshark ?p, ProSpar Comp 15 or RCF6)

- 4 ferrules to fit the carbon tubes

- 2 arrow nocks and adapters to fit the carbon tubes

- 3 vinyl end caps to fit the carbon tubes

- 4 molded leading edge fittings**

- 1 molded end cap to fit the lower spreaders**

- 1 molded end cap to fit the base of the spine

- 2 sets molded stand-off fittings**

- 18” shock (bungee) cord 1/8” diameter

- 9” shock (bungee) cord 1/16” diameter

- 24 of 0.109” (3mm) solid carbon rod

- 2 vinyl end caps to fit 0.109” (3mm) rod

- 15’ 135-lb-test Dacron line for bridle

*This design was developed to take specific advantage of the elastic properties of Carrington K-42 cloth. We cannot recommend substitutions.

**Or equivalent fittings from suitably drilled vinyl tubing.

Cutting

The grain line in the fabric is important to this kite, and the pattern is designed to the fabric’s best advantage. Carrington’s K-42 is a fairly stretchy fabric and if the pieces are cut without regard for this, you will see pulls and stretches in the finished kite that you didn’t expect or want. See the diagram for grain orientation.

Seam allowances must be added to the dimensions given. Add 1/2” on both sides of the seam where the screen meets the wingtip panels, and no seam allowance on the trailing edge of the screen section. Add 3/8” on all other seams, including the trailing edge and leading edge.

Probably the only thing you should be aware of when cutting Carrington cloth is that it has a definite wrong and right side. The sticky side goes to the back of the kite, so you need to flip the pattern over when you cut the right and left sides of the kite. If you ignore this point, you will have a sticky left side and a shiny right side of the kite.

Sewing

It is easiest to tackle the sewing on this kite if you consider it in three manageable sections: the center, mid-wing and wingtip. Sew each one individually before assembling into the final kite. If you haven’t worked with Carrington cloth before, you might be surprised by its stretchy nature and might want to practice with it before approaching the kite.

In joining the seams, place the right sides together, then fold the allowance over twice on the back of the kite and stitch it down. Some thought is required to fold the allowance towards the darker color for the sake of appearance. Now sew tighter:

First, the center section:

- Sew spine panel (A) to nose piece (B).

- Join (A) to (C) then hem their portion of the crossover opening.

- Join (D) and (E), then hem their portion of the crossover opening.

- Sew (C) to (D) and hem the trailing edge created along (C), (D), and (E).

- Join right and left center panels together. This should now be a flat panel. Youwill want to bartack or otherwise reinforce all four corners of the crossover opening.

- Attach the Dacron upper spreader reinforcement.

- Attach the Dacron strip along the spine below the lower spreader (because this seam is along the bias and will eventually stretch out this reinforcement).

- Sew the lace loop at the base of the spine to project 3/8” beyond the aft edge of the sail.

Second, the relatively easy mid-wing section:

Join the triangular piece (F) to the trailing edge piece (G), ensuring you have the proper sides joined. This you can indicate at the pattern stage so you don’t get confused at the sewing stage. Join these to the main wing panel (H), and hem the trailing edge.

Third, the wingtip:

This is the most difficult to sew. Join two wingtip panels (I) and (J)together, and then add the mesh. The mesh pattern is curved to allow extra length to be joined to the cloth. If this is not done, the mesh will tighten up the cloth and will be too short. This is part of what we have affectionately dubbed “pattern magic.” Some of these pattern and sewing principles we have borrowed from our tailoring days, and it seems like magic to the uninitiated!

Last steps:

You are now ready to join the wingtip section to the main section, and proceed to the mesh trailing edge. The hem on the mesh is accomplished with the addition of a strip of strong fabric to prevent stretching along the trailing edge. Fold the 1″ strip of 1.5-oz. nylon into four lengthwise folds, and stitch the mesh inside. There needs to be 1″ of mesh exposed for the vent to be effective in all winds. Here again, the mesh is longer than the finished length, so you must push the mesh inside the folded nylon to create the length you need. If you don’t get this the first time, rip it out and do it again.

This whole section is now ready to join to the center panel. Add the leading edge sleeve along with the ballistic nylon reinforcement at the wingtip, and the stand-off reinforcements. Peel the Kevlar tape and stick it to the center of the ballistic nylon nose to protect it from the spine rod, and sew the ballistic nylon to the kite. Once you trim and heat-seal the leading edge openings, nose and wingtips, the kite is ready for framing.

Framing

The assembly of the frame is typical of most good quality sport kites. We used custom molded plastic fittings, but suitable sizes of drilled vinyl tubing would work just as well.

We also used small pieces of vinyl tube as stoppers along the leading edge, to ensure that the molded fittings cannot wander out of position. These should be secured by a drop of cyanoacrylate (“super”) glue.

The leading edges are held under tension by 1/8” elastic shock cord. A hole for the cord should be burned through each of the ballistic nylon wingtip reinforcements. The reinforcement will keep the hole from elongating no matter how tight the shock cord.

The sail is tensioned along the spine with a lighter, 1/16″-diameter shock cord. It should be tied through the end of the milled cap and through the lace loop at the base of the spine. The result is that the spine extends only 5/8″ below the sail, but can be adequately tensioned and disassembled as needed.

In our prototypes we used the usual 0.098″ carbon rod for stand-offs, but these broke repeatedly. The stand-offs are significantly loaded as they help maintain sail tension. The kite was so good at ground work that we were tempted into performing tricks that were too much for the stand-offs to withstand. Once we switched to 0.109 (3mm) solid carbon stand-offs, the problem disappeared.

Bridling

The bridle is a simple three-legged arrangement. We like to tie loops from 8″ lengths of string, then lark’s-head-knot these around the fittings at the crossover and along the leading edge. The four bridle lines can then be attached to these loops by more lark’s head knots. This arrangement allows us to switch bridles, or attach several experimental bridles at one time.

Flying

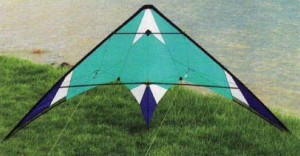

The Tekaweya is an agile kite for its size and flies in a wide range of winds. Its tight turning and fast forward speed challenge you to fly it well and with persistence it will ultimately improve your flying. We have been flying Tekaweyas for over two years, and they remain among the favorites in our kite bag. We hope it will be a favorite for you too.

This article was reprinted with permission from Volume 11, Issue 4

(Winter-Spring 1996) of Kite Lines magazine, available in our archives.