To help celebrate the release of the Drachen Foundation’s Wings of Resistance, The Giant Kites of Guatemala, I’d like to write this month about some of the very sophisticated kitemaking techniques which are used, but easily overlooked, in the creation of these giant masterpieces. Certainly, these kites are a direct reflection of their environment both in construction materials and in their social and political contexts. Papel de chine (Chinese paper or tissue paper) is an inexpensive sail material that also allows enormous artistic freedom. Bamboo, gathered from coastal areas where it grows best, directly limits the size of the largest kites: 8 to10 meter lengths of bamboo can be spliced together only to the limit of about fifteen meters, for the overall width and height of a finished kite. Social tradition dictates that the kites exist for only one day; previously they were ceremoniously destroyed, but today the sails are kept as a living archive of this unique kite culture. Finally, overt messages, representational motifs, and artistic expression are a direct result of both the political situation in Guatemala and the artistic evolution of the barriletes’ artists.

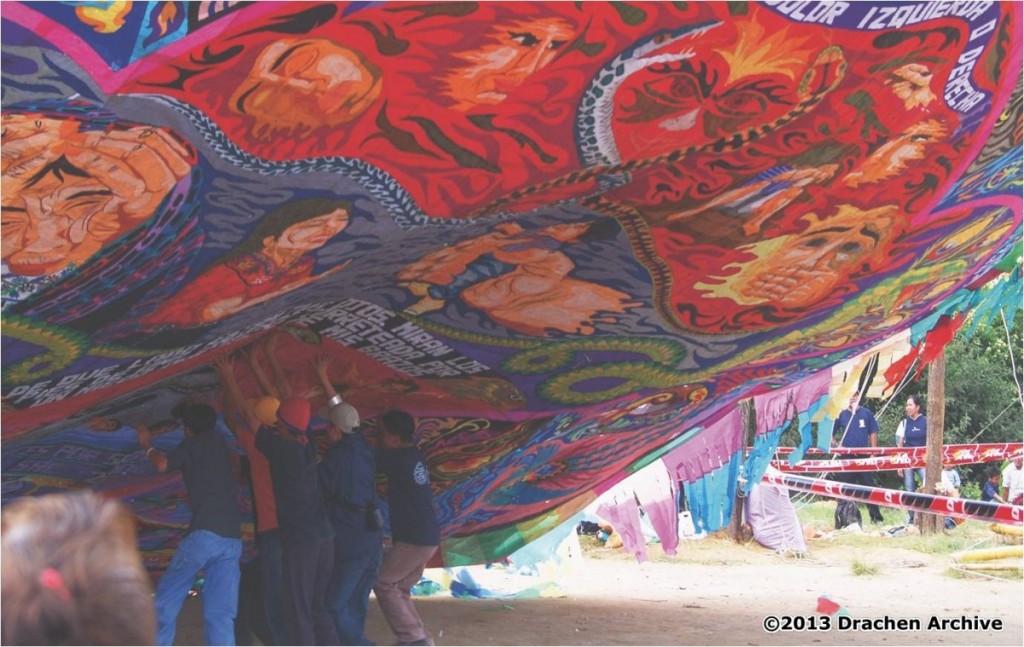

To clarify, these giant kites do not fly on the Day of the Spirits. Again, environment plays a major role: winds at this time of year are typically very light, but more important is that the barriletes draw such large crowds, the kites cannot be safely launched and retrieved. Despite this, having watched the teams prepare their kites, there is no doubt that they are made to fly, and would, in proper conditions, fly very well. These are flat kites flown with very long tails – nothing magic about their flight-worthiness, just that combination of lift and drag that works for the simplest of hexagonal or octagonal kites. In fact, I recall that the “formula” used for Nantong, China whistling kites – another heavy flat kite made stable with tails – has tails weighing exactly half the weight of the kite. The “formula” for the barriletes might be similar.

One indication to me that there is care taken to make these kites flight-worthy is the construction of the bamboo frame. Certainly these frames are very heavy in relation to their sail area, that is the nature of the thick-walled bamboo that every team uses. But in securing the sail to the frame, great care is taken to ensure that each spar end is exactly the same distance apart, helping to make the frame as symmetric as possible. This symmetry is “measured” by drawing a rope around the circumference of the frame and, if the frame has 16 points, the rope is then folded in half four times. The 16 lengths give the exact length between spar ends. The spar ends are then tied and wired to the exact point where they should be, resulting in a nearly symmetric frame.

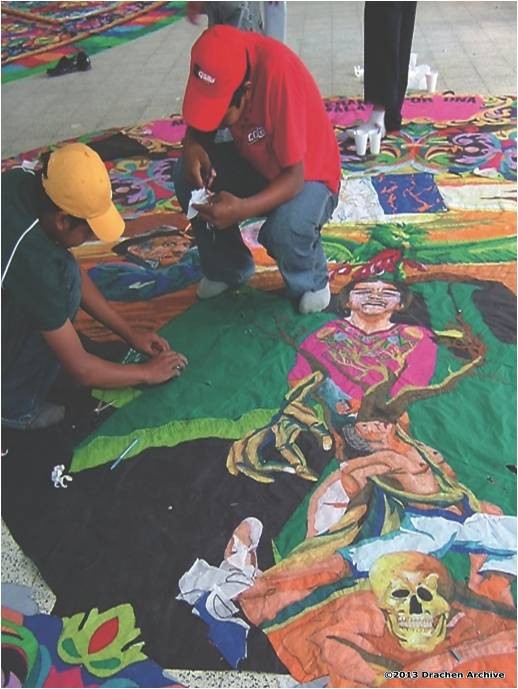

The most obvious sophistication in the barriletes is demonstrated in the amazing applique paper techniques that produce almost photo-realistic imagery. Over the years, teams have refined their layering techniques to produce almost any color. As important as the layering is, the gluing of the layers is just as important. Glue can be evenly applied for a straightforward shading effect. It can also be stippled, striped, or patterned to produce a variety of visual effects: texture of plants’ leafs, realism of fabrics and clothing on characters, or simply, another layer of color within the two layers of paper.

Translating an original drawing to the size necessary for a barrilete is no more difficult than making the original drawing on graph paper and then up-sizing to the final size wanted. This up-sized drawing is made on butcher paper so that the final sail can be pieced over it, ensuring accuracy of the final image. Additionally, from the original small scale drawing, sections can be cut away and the repeating patterns can be assigned to team members to do in their own homes. The final sail will only come together in the last days before the festival. Just like a single kitemaker working in his own studio, a number of factors are at play here to influence the final product. For a kitemaker, there is concern of material costs, of deadlines, and of marketability. For the barriletes teams, concerns are similar; there is always great financial pressure to gather materials necessary for their kite, and their deadline is unbreakable. The frenzy of activity in the last few days before the Day of the Spirits is one of the highlights of the entire tradition. The kites are not for sale or reproduction. They are pieces of fine art, only to be judged by their peers (fellow kitemakers), appreciated by their followers, the indigenous people of Guatemala, and very few foreigners, from all parts of the world, who have ventured to Guatemala to experience the splendor of this great tradition.

The kitemakers and their art have been documented in Drachen’s latest publication, Wings of Resistance, The Giant Kites of Guatemala. This publication was made possible by the generous support of Drachen Foundation Publishing Patrons.

Copies may be ordered through the DF store at:

Thank you for reading,

Scott Skinner