International Mokuhanga Conference, 2011

I recently had the opportunity to address the participants of the first International Mokuhanga Conference, held in Kyoto, Japan.

The subject was one that I assumed the participants (mainly professional woodblock-print artists and educators) had not encountered before which was the use of woodblock prints by kite makers in old Japan. If you’re not familiar with the term “mokuhanga”, and I wasn’t until recently, it describes the process in which woodblock prints are made by printing onto damp washi (Japanese handmade mulberry paper).

The subject was one that I assumed the participants (mainly professional woodblock-print artists and educators) had not encountered before which was the use of woodblock prints by kite makers in old Japan. If you’re not familiar with the term “mokuhanga”, and I wasn’t until recently, it describes the process in which woodblock prints are made by printing onto damp washi (Japanese handmade mulberry paper).

Mokuhanga was a process used by Japanese kite makers to help speed up production for their most inexpensive models. It makes sense that this would be the process for smaller kites, where relatively small blocks could be used to print a sumi (black ink) image that could then have color added for the final product. To introduce this history to professional woodblock artists was a great outreach opportunity for the Drachen Foundation and to further illustrate the idea, we collaborated with the Kyoto International Woodblock Association (KIWA), Hiromi Paper International, and McClain’s art supplies to produce a kite exhibit which ran during the KIWA exhibition just prior to the Mokuhanga Conference. Prints were solicited from print artists and kite makers  from North America and beyond and were sparred in Colorado before traveling to Japan.

from North America and beyond and were sparred in Colorado before traveling to Japan.

I find it interesting that here is an object, the kite, seen in historical woodblock prints, often made with woodblock printing techniques, and which can now be made by contemporary artists using this same historic technique. The kite is in the center of an art movement that has come full circle; from an outdated and neglected art form to a new cutting edge print technique attracting a worldwide following.

International Mokuhanga Conference, 2011

Kites in Japan and Their Close Ties to Mokuhanga

Kites are first mentioned in Japan in the Hizen no kuni fudoki, a compilation of records begun in 713, and in the Nihongi, a chronicle dating from about 720. In a Japanese dictionary compiled in 930, the Wamyo ruiju sho, two words for kite are given: shiroshi and shien. Both of these words can mean paper hawk, and the first kites in Japan may well have been paper and bamboo constructions in the form of a hawk. These kites, shaped like the letter T, with long wings and a small body, are aerodynamically viable and lend themselves to representations of birds, insects, and even humans. We will see derivations of this shape throughout the ukiyo-e (print movement) with images of kites such as the tombi, yakko, and phoenix.

Nara bureaucrat Minamoto Shitago, who worked in the department of Shinto and the Bureau of Divination compiled the Wamyo ruiju sho. This suggests the religious and ritual connotations of Japanese kites, as they came alive in the wind and energetically carried “prayers” up to heaven. Two priestly families of the Shinto Grand Shrine of Izumo flew kites in the shape of the character for tsuru, crane. The crane was believed to live for a thousand years, so the kites symbolized their longevity. Kites were flown in the countryside during the springtime as prayers for good harvests, and it was believed that the harvest could be predicted by a kite’s flight and the direction from which it fell out of the sky. In Hoshubana, a place still famous for its large kites, a kite’s flight was believed to forecast the year’s silkworm production. Kites were flown in the autumn with stalks of rice tied to them to give thanks for a plentiful harvest.

Nara bureaucrat Minamoto Shitago, who worked in the department of Shinto and the Bureau of Divination compiled the Wamyo ruiju sho. This suggests the religious and ritual connotations of Japanese kites, as they came alive in the wind and energetically carried “prayers” up to heaven. Two priestly families of the Shinto Grand Shrine of Izumo flew kites in the shape of the character for tsuru, crane. The crane was believed to live for a thousand years, so the kites symbolized their longevity. Kites were flown in the countryside during the springtime as prayers for good harvests, and it was believed that the harvest could be predicted by a kite’s flight and the direction from which it fell out of the sky. In Hoshubana, a place still famous for its large kites, a kite’s flight was believed to forecast the year’s silkworm production. Kites were flown in the autumn with stalks of rice tied to them to give thanks for a plentiful harvest.

Kites could be bought at both Buddhist and Shinto temples and shrines as charms against sickness and misfortune. Kites were flown for good luck on many occasions but became particularly associated with the New Year and with Boys Day.

Without losing its quasi-religious connotations, kite flying became a more secular pastime in the 18th Century. Boys flying kites for fun are seen in two genre paintings from the early 18th Century, Scenes Around the Capital (Kyoto), a folding screen attributed to Tosa Daijo Genyo; and The Way to the Yoshiwara by Okumura Masanobu.

Without losing its quasi-religious connotations, kite flying became a more secular pastime in the 18th Century. Boys flying kites for fun are seen in two genre paintings from the early 18th Century, Scenes Around the Capital (Kyoto), a folding screen attributed to Tosa Daijo Genyo; and The Way to the Yoshiwara by Okumura Masanobu.

An illustrated encyclopedia titled Wakan sansai zu-e of 1712 shows a kite with five tails, a line, and a reel. Its characters read ikanobori, squid flag or banner.

But the ritual significance and symbolism of kites persisted, to the extent that flying a kite successfully was used as a metaphor for ruling the nation.

The New Year celebrations of 1784 required that the shogun, Tokugawa Ieharu, fly a 12 foot wide kite, painted by the head of the official Kano studio, with auspicious designs of cranes and pine trees. As Ieharu was flying the kite, a gust of wind tore the line from his hands.

Four retainers who tried to hang on to the line were lifted and thrown to the ground; three died. Out of control, the kite narrowly missed striking the shrine of the shogunate’s founder, which would have been inauspicious, indeed.

Four retainers who tried to hang on to the line were lifted and thrown to the ground; three died. Out of control, the kite narrowly missed striking the shrine of the shogunate’s founder, which would have been inauspicious, indeed.

After this experience, the State Council decided that the ritual should be abandoned.

Kites flourished in the 18th century and into the 19th century there was a kite mania throughout the country. Enthusiastic kite flying sometimes led to scuffles and brawls. As early as 1655, the government restricted kite flying within the capital; that the edict was ineffective is suggested by a similar one issued the following year. Both woodblock prints and kites were affected by the sumptuary laws of the 1780s that outlawed extravagant decoration of kites (for example, with gold and silver) and prohibited privately published calendar prints. Calendar prints, egoyomi, were considered a monopoly of the government and indicated the long and short months of the coming year.

In 1796, the Morozakiya establishment in Funamatsu-cho began selling large kites that were made with more than two sheets of paper brightly painted by professional artists. Prices were very high, but spoiled children were said to want only the Morozakiya kites. The neo-Confucian government of the time frowned upon this wasteful spending since it assumed a zero-sum economy where consumption in one field meant an overall loss to the whole. Local daimyo tried to encourage thriftiness; for example, in 1807 the lord of Hamamatasu Castle decreed that kites should not be ostentatiously decorated or more than four feet square. Edoites were traditionally contemptuous of authority, and kite flying itself could be a mild form of rebellion against a strictly stratified hierarchy. Commoners loved to fly kites over the compounds of noble families in Edo, and though not specifically forbidden, it was considered a way to thumb the nose at social superiors.

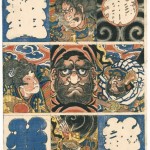

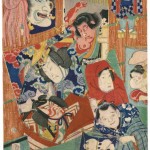

The parallels in the history of Japanese kites and ukiyo-e continued into the 19th Century. The Tempo reforms of the early 1840s included restrictions on both the sale of large painted kites and the number of colors used in woodblock prints. Actor prints, yakusha-e, were specifically banned temporarily putting the figure painter and print artist Kunisada out of a job. Kuniyoshi, his rival, found imaginative ways to illustrate actors, including putting their faces on kites. High profile artists, publishers, and actors were vulnerable to vindictive officials. Utamaro and Kuniyoshi were both arrested at different times for ignoring the government’s inconsistently applied restrictions on the subject material of woodblock prints. Successful actors, often rich and vastly popular but of low social status were also at risk.

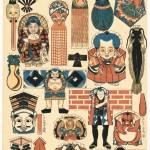

Throughout the 19th Century, ukiyo-e give an indication of the popularity of kites. In a number of New Year’s prints, kites are shown as a popular toy and as an expression of admirable traits for young boys to aspire to. They are shown flying over rice fields after harvest and in cities at festival time. In omocha-e by the artist Yoshifuji, popular kite shapes are to be cut out and played with by small children. Numerous ukiyo-e show popular kite designs of the day: airborne kanji (ji dako), fireman standards, Kintaro, Daruma, cranes, dragons, squid, octopus, and heroes. An Edo boy growing up in a culture steeped in tales of Japan’s rich history would have immediately recognized these figures. Each was a model of courage, strength, perseverance, or some other manly virtue.

Throughout the 19th Century, ukiyo-e give an indication of the popularity of kites. In a number of New Year’s prints, kites are shown as a popular toy and as an expression of admirable traits for young boys to aspire to. They are shown flying over rice fields after harvest and in cities at festival time. In omocha-e by the artist Yoshifuji, popular kite shapes are to be cut out and played with by small children. Numerous ukiyo-e show popular kite designs of the day: airborne kanji (ji dako), fireman standards, Kintaro, Daruma, cranes, dragons, squid, octopus, and heroes. An Edo boy growing up in a culture steeped in tales of Japan’s rich history would have immediately recognized these figures. Each was a model of courage, strength, perseverance, or some other manly virtue.

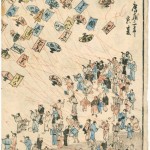

The sophistication of kite design can be seen in many of these “kite prints”, but they are best illustrated in Kunichika’s, Modern Parody of a Kite Store. Hanks of line, scissors, hummers (unari), and line winders are shown with the popular kites of the day (1865). Here we see ji dako, tako tako, tombi dako, yakko dako, and a variety of rectangular Edo dako. The effectiveness of the kite as political tool can be seen in Sadahiro’s Today’s Rising Kites (Tosei nobori ika), printed in the waning years of the shogunate when the Japanese economy was highly unstable. Each of the many kites has a character on it signifying some household item or service. Everything from everyday life is here: paper, oil, tea, tabi, miso, geta, nori, beans, books, brushes. The money market kite lies supine on the ground.

Japan’s love of kites continued into the 20th Century, and the traditions of many of the kite centers are seen in postcards published prior to World War II.

Japan’s love of kites continued into the 20th Century, and the traditions of many of the kite centers are seen in postcards published prior to World War II.

The distinctive round kites of Naruto are found in photographic postcards as are the fighting hata of Nagasaki. The large rokkaku kites from Sanjo are seen with their kite teams and the giant kites from Shirone are shown battling over the river between Shirone and Ajikata.

Kite enthusiasts throughout Japan keep traditions alive through the Japan Kite Association and local groups in kite flying hotbeds like Shirone, Hamamatsu, and Sanjo. Currently, one of three “world’s largest kite” resides in Tokyo and is flown by Japan Kite Association president, Masaaki Modegi. Likewise, the record world’s smallest kite is made by Kyoto’s Nobuhiko Yoshizumi.

Having seen the close relationship between Japan’s kite history and the development of ukiyo-e, it is appropriate that members of the International Mokuhanga Confernece explore possibilities of kites and prints.

Having seen the close relationship between Japan’s kite history and the development of ukiyo-e, it is appropriate that members of the International Mokuhanga Confernece explore possibilities of kites and prints.

The kitemaker of the 1800s used woodblock prints to increase the production of smaller, inexpensive kites, probably sold to children.

But it can be assumed that larger, special art kites were started with a special woodblock print and then hand painted for a particular customer. For this conference, prints were submitted by a variety of international print artists have been made into kites by Scott Skinner and Nobuhiko Yoshizumi.

The soft, translucent color that makes mokuhanga a distinct and special art form comes alive in kites. The kites follow traditional American and Japanese kite forms and are contemporary adaptations made to fly.

These collaborations should be viewed as functioning kites as well as examples of mokuhanga.

-Scott Skinner